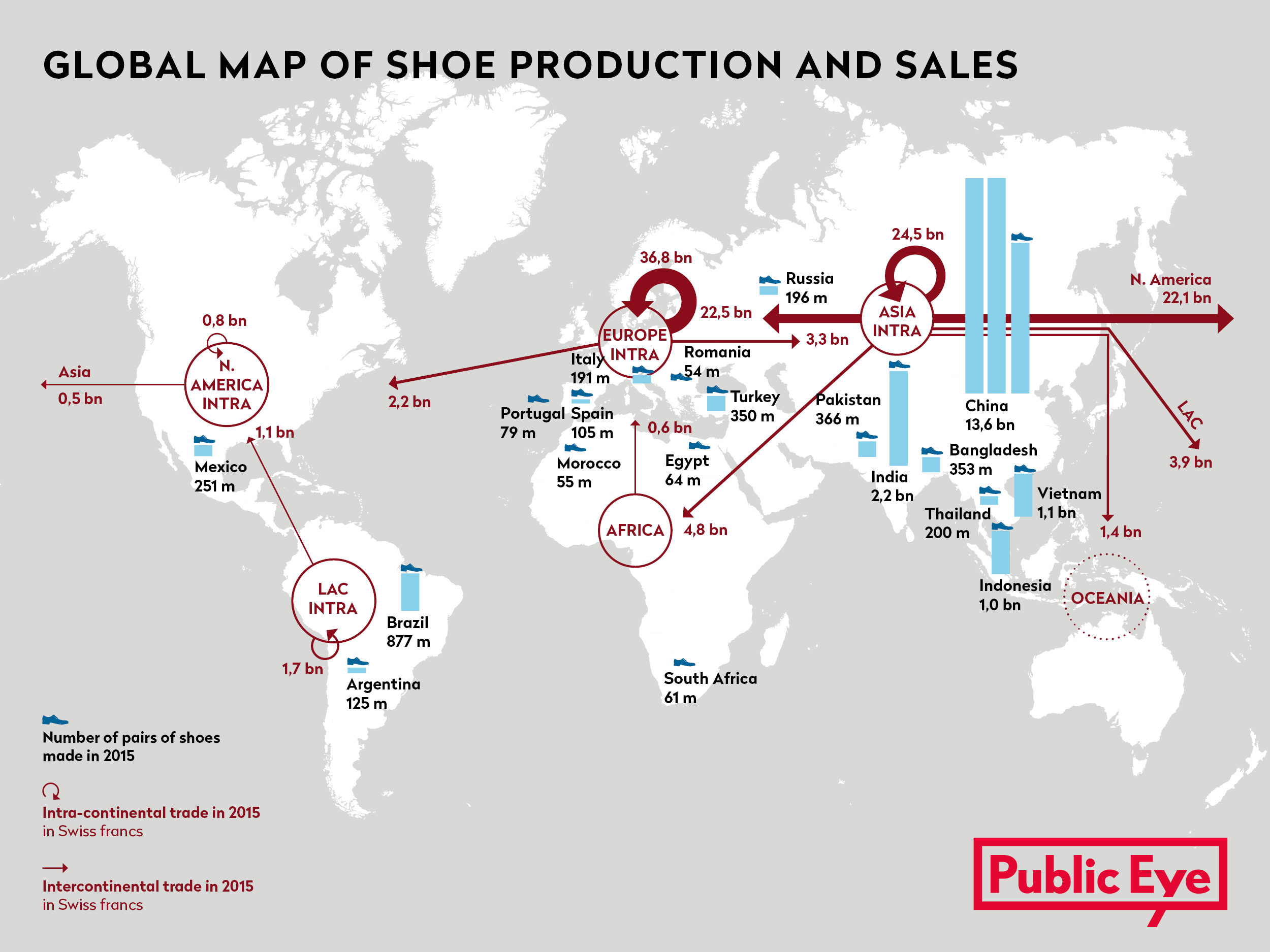

In 2015, over 23 billion shoes were manufactured worldwide. This comes to more than three pairs per person. If you live in Switzerland, and are an average consumer, you probably bought six or seven pairs in the last twelve months.

The time when shoemakers carried out the delicate work of repairing our good Sunday shoes has long since passed. Eighty years ago, Swiss households spent an average of 37 francs a year on their shoerepairs. This sum accounts for a mere 17 francs today, at a time when the average household income has increased twenty-fold. This industry has also now adopted the model of fast fashion. The rate at which collections appear no longer follows that of the seasons, and shoes that are sold at cut-price rates are no longer made to last. Shoe repairs and cobblers are out of fashion, and people simply prefer to throw a worn-out pair away, and buy a new one.

We lost track of where our shoes are made a long time ago. And the workers in the factories have no idea where the shoes will be sold. Nor do they have the slightest idea how much we will be paying for «their» shoes, and we have no idea of how much they earn.

They are not informed when we throw the fruit of their labour into the bin, sometimes without even having worn the shoes they made. We know nothing about those who made our shoes, are unaware of the amount of work it involves, or the number of different people involved, where they are based, or their working conditions. We set out to find the answers to all of these questions.

In the beginning was the cow

Statistics show that China leads the global shoe manufacturing industry, accounting for 60% of the worldwide production. They are followed by India at barely 10%. And we are sure that you are already aware that the big name brands buy their stocks at the lowest prices from Asian countries where the wages are very low and working conditions often unacceptable. This is why we decided to examine the production conditions for relatively high-end leather shoes, be they labelled «Made in Italy» or «Made in Germany».

Things generally start with a cow. Most leathershoes are made of cow or calf-hide. The United States, China and Brazil are the countries that produce most leather. The industry is happy to present the tanning industry as a way of «valorising» the by-product of the meat industry, notorious for its consumption of resources. This is a lopsided argument, as the two sectors are one and the same.

The Brazilian multinational corporation JBS SA. is the biggest meat-producing company in the world. Not only do they slaughter some 110,000 pigs, 80, 000 cattle and 14 million poultry a day (yes, you read those figures correctly, it does say on a daily basis), they also own and run 20 tanneries around the world.

Once the cow has been slaughtered, let’s move onto the leather. We’re off to Italy, the second biggest global exporter of leather shoes after China, and with a high quality – and price – reputation for its products. Italian tanneries are spread over three main districts. The first specialises in leather for shoes, bags and jackets. It is Santa Croce sull’Arno in Tuscany. Their prestigious clients include big name brands such as Prada, Gucci, Louis Vuitton and Burberry. We go to investigate on site.

And as soon as we arrive in the small town of Santa Croce, we soon see how people make a living here: walk up the main street, Calle di Via di Pelle (Hide Street) and turn down a side-street, Via Dei Conciatori (Tannery Street), near Via del Bottale (the huge vats used for tanning the hides).

«Not good for our health»

The air is heavy with the sulphurous smell of rotten eggs that comes from the hydrogen sulphide used in tanneries. Thousands of raw hides lie on pallets, salted but not skinned, spattered with dung and piled up in the open air. The owner of one of the 200 tanneries operating in the town is happy to show us around, to show us where the deadly stench comes from. He opens the hatch on one of the vats hanging in the warehouse, and invites us to follow him. Hundreds of hides are swimming in a greyish liquid. Where the hair had been, only a few small, sticky, blackfibres remain. The chemical products have dissolved the hairs.

Inside the tannery, bags and vats of chemical substances are stored on pallets. On the ground lies a puddle, with foam resting on top.

Our heads start to hurt, and we get dizzy. «No, it isn’t good for our health», admits the boss, «but that’s just how things are».

Respiratory problems, irritated skin or even lung cancer or cancer of the bladder are frequent side effects of the constant contact with the chemical products. But these chemicals are not the only danger to health: there is also the sheer weight of the hides.

«Africans never fall ill»

Once the hides have been limed, they are skinned and split in one of the companies in the same neighbourhood. We walk into one of these brick hangars that have corrugated iron roofs, and witness a somewhat apocalyptic scene.

Everything we can see here is the same colour: a sort of oily greenish-grey, with the occasional bluepatch. Hides are piled up everywhere. Everything is slimy and if you are not careful, there is the risk of slipping and falling at every step you take. The noise is exasperating and the air hangs heavy with grease. A mechanical digger lifts the skins and deposits them on a platform where a Ghanaian, an Italian, a Moroccan and a Senegalese are busy working two machines. The managing director of the company explains that he hasn’t hired Italians for years.

«There are far fewer problems with Africans. They are hard workers. They never fall ill. Italians no longer want to do this kind of work».

An unsavoury display

Four men dip their hands into a barrel full of sawdust, and grasp a hide from the pile behind them. They lift it, and feed it into the machine that scrapes off any remaining flesh. On another machine, the splitting process occurs: the upper part will be tanned and become leather, whereas the lower part slips through the wall into a red container situated outside the building. On the container it says: Materia Prima per la Produzione di Gelatina destinata al consumo umano. It does not appear particularly appetising. Seen from outside, it looks as though the building were vomiting, spewing out this mass destined to produce gelatine for food …

So the leather has been tanned and is sent on to small family-owned companies in Sana Croce sull’Arno, where it is died and rolled up. It is time to start making the shoes. You might think that this stage takes place in Italy for shoes labelled «Made in Italy», or in Germany for those with a «Made in Germany» tag. But this is often not the case.

Destination: Albania

This is the result of a production model known as outward processing trade, that allows companies to export semi-finished products such as shoes, that are then made in another country and reimported once they have been finished, without paying import duties on them. Thus it is Poles, Slovakians, Rumanians, Macedonians or Bosnians – and essentially women who work in these factories – who make millions of pairs of «German» or «Italian» shoes every year.

An international public enquiry carried out by Public Eye highlighted that they fail to earn enough for their families to lead dignified lives. The least paid are the Albanians, who work mainly for Italian brands.

In Albania, the minimum legal wage is 150 Swiss francs a month, which is below the level of neighbouring countries, and even lower than the rates paid in China!

In the Tirana slums

How can you meet a family’s needs on just 150 francs a month? Arjana Bajrami (this is not her real name) is the living proof that it is possible, one way or another…

Worn from the life she leads, she looks more than her 32 years.

Arjana lives in Bathore, one of biggest slums in Tirana, together with her husband and their two sons, aged seven and twelve. On the dust track that leads to the Bajrami’s house, old Mercedes creak along, and an old man burns his household rubbish by the wayside.

Arjana invites us into her living room, which is the only room that is heated by the wood-burning stove. She offers us a mint sweet, prepares coffee on a camping gas cooker, and starts to tell us her story. Four years ago, her elder son, Rigers, was hospitalised for a faulty heart valve. An operation was needed. This was going to cost 5’000 Swiss francs. The Bajrami managed to raise this huge sum from friends and relatives, but they are far from being able to pay it back. Then her husband lost his job, and two years ago, Arjana decided she needed to travel the few kilometres to the factory, to ask for work. She was hired on the spot.

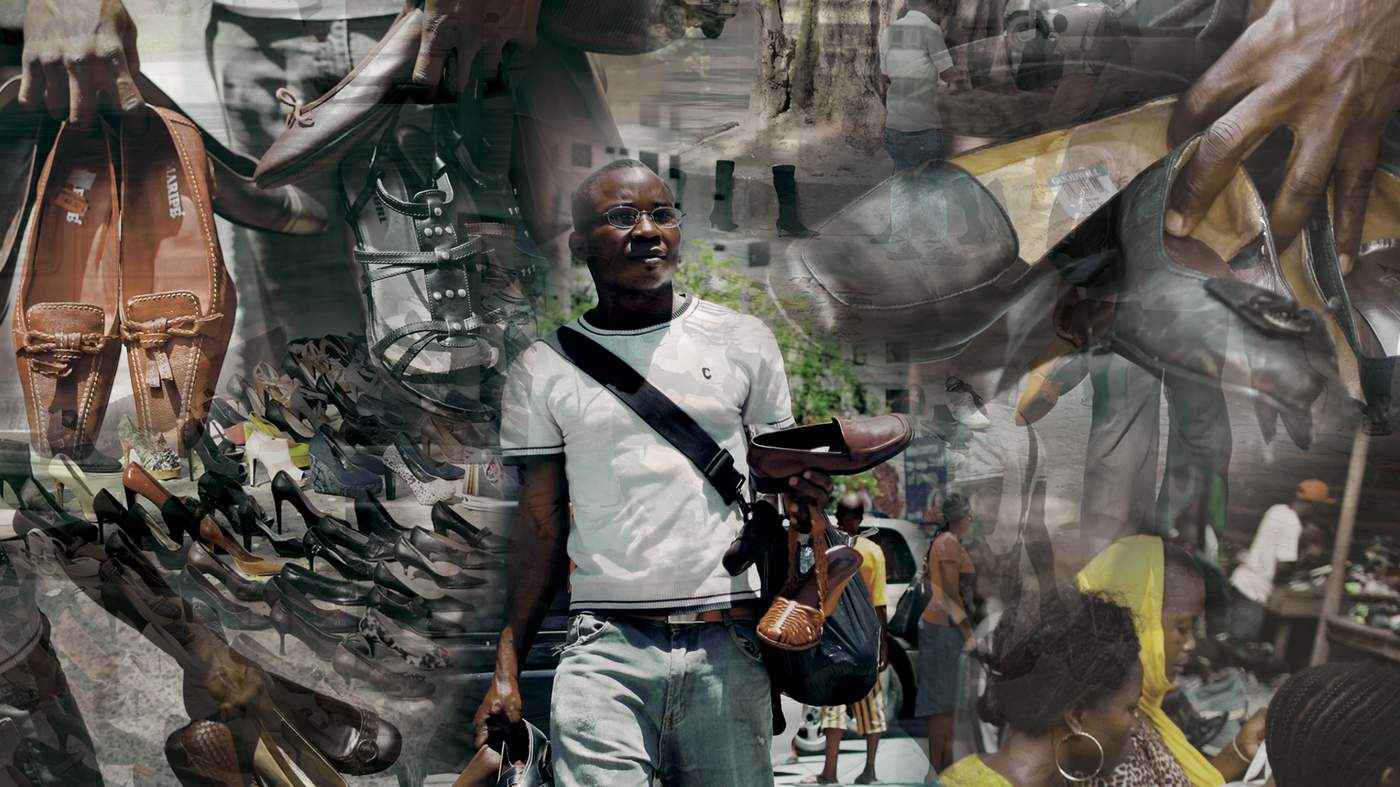

Resigned to her daily lot

Her job consists of smearing glue on the toe protection at the front of shoes, placing it in the oven for a few seconds, and then sticking it onto the leather. «The worst part of this is the smell of the glue», she says. She does not wear a mask. «I find it so hard to breathe already». The glue causes drowsiness, and she often has headaches. «But I am hanging in there». Arjana does not know what brand she is working for. The shoes she makes are sold for over 200 euros – more than her monthly salary. The winter boots that she wears are made in China, and cost her less than 2 francs. She bought them from a travelling salesman.

Debt ridden

Arjana works every Saturday, and sometimes even on Sundays. She gets up at 5.30 AM, and prepares breakfast for herself and her sons: bread with scrambled eggs and cheese; this is often replaced by a slice of bread and margarine at the end of the month. She then walks to work, and doesn’t get back home until after 4 PM. She then prepares the dough for making her bread, if she has not run out of flour, like now. The electricity bills and the cost of the cubic meter of the firewood she uses so sparingly, allow Arjana to heat the house for the month, but eat up two thirds of her pay. Her two sons have never eaten in a restaurant. They have never even visited the city centre of Tirana. «The bus costs too much«, explains their mother «and anyway, they would only see beautiful things that we can’t afford to buy them».

What are Arjana’s dreams for the future? She hopes that her sons will remain in good health, that she will be able to get the leaking roof of the house fixed, and that her husband will find a new job. But more than anything else, she wishes that she could leave, and lead an easier life with more hope for the future for herself and her sons. But she doesn’t know where she would go.

Read the full history of shoe making in Albania here (only available in German language)

Prison-like factories

From afar, Arjana points to the factory where she works. She doesn’t want to be seen in our company, for fear of losing her job. Most of the factories look like prisons, surrounded by high walls and protected by guards. The names of their clients are generally a close-kept secret, as is the list of their employees, because informal labour is so widespread. Buses bring the workers to the factory every morning, and transport them back home after work. We do not gain entry to the factory where Arjana works.

But we do manage to slip into another factory, in the port city of Durrës. It is cold. The noise level is deafening. The smell of glue hangs heavily on the air. On this particular Friday in January, there are around 200 people – mainly women – working in the factory, and they are all wearing thick coats.

Almost nobody is wearing protective gloves, because they all need nimble fingers to do their job.

Like the young man who talks to us, at the same time as he absent-mindedly feeds leather into a battered, outmoded machine. It is a vision that gives you the creeps. Further along, three women are spreading glue on leather for the shoes. The fumes seem unbearable to us. But they are not wearing masks.

«Made exclusively in Italy»

At the very back of the factory, enormous machines are worked by men. The workers place metal shapes on the leather or plastic and then use a huge «press». The operation is repeated until only shreds remain. In another part of the factory, there are women seated facing a conveyor belt, working on a production line. They make the same gestures, repeated non-stop throughout the day, surrounded by the noise of the machines, and never exchange a single word. In an adjacent room, two men are working at a table where a candle burns. The first cuts 3-centimeter strips from a roll of plastic. His colleague burns both ends, using the candle, and then presses them together for a few seconds so that they stick together. These are the eyelets through which the laces are then threaded.

The shoes that are made here are for a brand that boasts that the products it sells are «made exclusively in Italy» in «the most modern production units».

The workers, both men and women in these factories, have absolutely no idea where the shoes they make will be sent. And we know nothing about those who have made the shoes we wear. The shoe manufacturing industry is a shady, globalised sector that makes money for shareholders of the big brand names. The workers pay for this with their health, in exchange for a pittance, so that consumers can make the most of the «special offers» that they buy, often without wondering who is bearing the true cost of their production.

For Public Eye, this situation needs to change. But how?

Brands and shoemakers need to assume their responsibilities, especially through the following measures:

• Pay a minimum living wage that will allow employees in factories and their families to live dignified lives

• Protect health and ensure the safety of all personnel

• Implement transparency, stating the names of the suppliers and sub-contractors, and showing the steps taken to guarantee fair working conditions

Political decision-makers need to ensure that there are binding rules that:

• Ensure minimum wage levels are set to meet basic needs

• Enact and implement labour law and human rights

• Oblige companies to examine risks and implement accountability and transparency as well as take effective measures to protect human rights

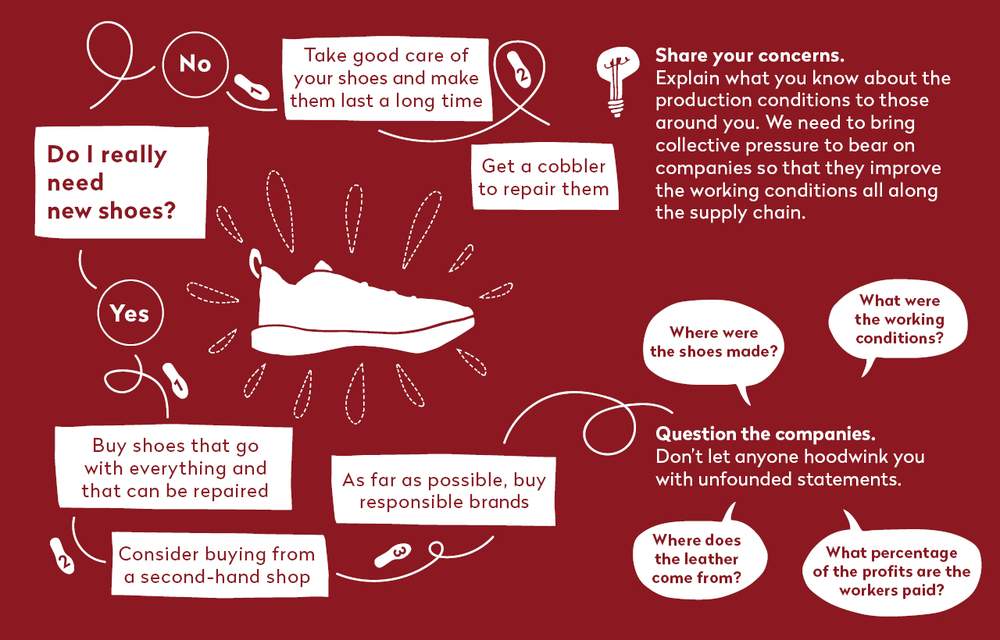

We can take good care of our shoes, get them repaired, buy second-hand shoes or buy them from responsible suppliers as far as possible. Our consumer choices mean that we can refuse to give in to the dictatorship of brands and fashion. But this is not enough.

As consumers who are aware of the values of justice and equity, we can try to understand how this industry operates and make the brands face up to their responsibilities and demand justice and equity in the way in which our shoes are made.

Public Eye has created a tool that demonstrates how important ethics are in making shoes. And you can join our awareness-raising campaign: Create and win the ethical shoes of your dreams at www.theshoecreator.ch. Invite all the shoefans you know to use Shoe Creator to raise their awareness about production conditions.

Create and win the ethical shoes of your dreams at www.theshoecreator.ch

Through research, advocacy and campaigning, Public Eye demands the respect of human rights throughout the world. With a strong support of some 25,000 members, Public Eye focuses on global justice. Support our work: donate now!